[ad_1]

As gripping as a novel, as atmospheric as a video game. It’s a unique balance that Argentinian developer duo Fer Martínez Ruppel and Nico Saraintaris of LCB Game Studio aims to strike through its interactive novel series, Pixel Pulps. “Being on the margin validates us”, LCB says. “When we created the Pixel Pulps, one of our goals was to create a new genre, to stand at a specific point in time and not just imagine an alternative line of development, but to create it.”

This “new genre” in question occupies the curious space between horror game and horror novel. As someone with a keen interest in the evolution of horror games leading up to and including the current horror game renaissance, the concept of a brand new subgenre piques my interest immediately. “Our games are not first-person – they require a lot of reading, they don’t have incentives for endless play sessions, and yet, streamers from all over the world play them and share them in something that feels more like a group read than a playthrough,” says LCB.

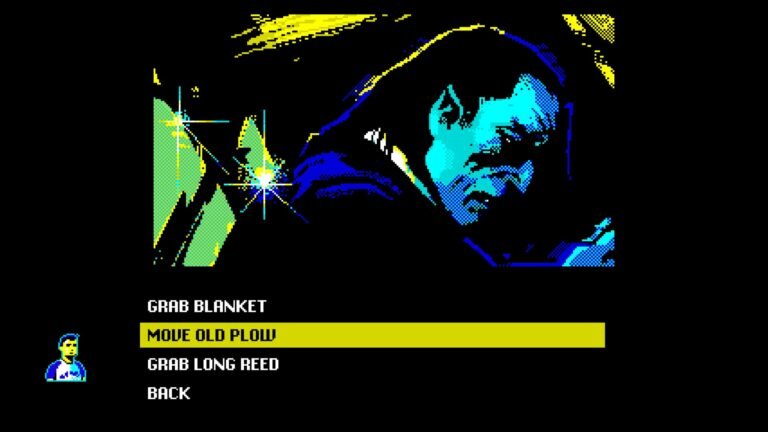

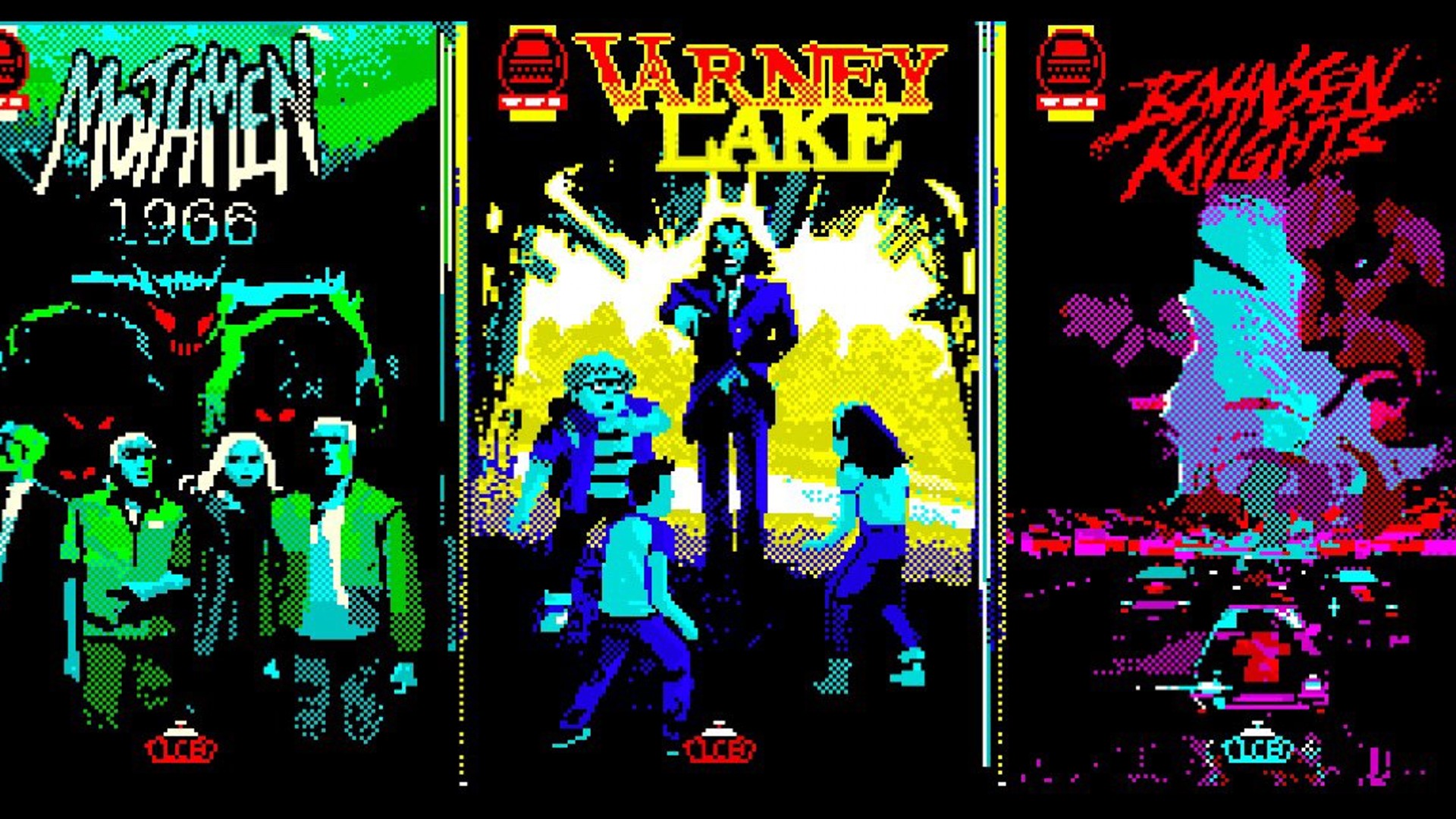

Pixel Pulps are interactive visual novels with light puzzle elements, heavy on both the novel and novelty, that share CGA graphics and point-and-click gameplay. At the same time, LCB somehow captures a very specific feeling: sitting down to read a dog-eared copy of an obscure horror story, plucked from the shelves of a dusty library that few still frequent. This commitment to literary storytelling runs through each of the three existing Pixel Pulps because LCB Game Studio wasn’t always a video game developer.

The hint is in the name: LCB – abbreviated from “Literatura Clase B”, or Class-B Literature – published illustrated stories once upon a time, but now, it’s determined to make waves in one of the busiest games genres around.

Page churning

It all started with Atlantis. Martínez Ruppel and Saraintaris describe themselves as a “creative duo”, with a shared love of literature, horror, and storytelling that culminated in their first collaborative project back in 2012. “In our case we feel like we are a footnote in a perhaps more organic and normalized horror game development history,” they explain.

As unquantifiable as normalcy might be in the weird and wonderful world of game development, I don’t think LCB is wrong in saying so. Going from creating illustrated stories like ‘The Atlantean Butcher’ – “picture an exiled Atlantean struggling for survival on the mainland” – to a series of 8-bit-style horror games in the space of nine years probably isn’t the weirdest studio origin story out there, but it certainly stands out. It also explains LCB’s continued dedication to crafting literary experiences through video games, even after the studio merged its creative channels in 2021. To this day, LCB treats game dev as a mid-20th century publishing venture: “Publish, publish and publish even more.”

But why horror stories specifically? “We are interested in genre fiction in general, and within this enumeration, horror has a very special place,” LCB says. “Horror is the constant threat of the tale’s emergence: A boat trip on a lake may seem trivial, but there is always the possibility that the tail of a creature we can’t see will turn it upside down, transforming a simple trip into something worthy of being told.” It’s this catalytic potential of the horror genre that, according to LCB, “transforms a simple concatenation of words into a story. Horror is the alchemist’s secret, if you will.”

Whether it’s the ominous tail of a fabled aquatic beast or the mangled form of Jason Voorhees bursting from the watery depths, LCB Game Studio knows what makes horror fans tick. Each Pixel Pulp is decidedly retro in nature, and each hones in on a specific horror trope. Mothmen 1966 is all about cryptids, my personal favorite Varney Lake is a retro-gothic vampire adventure, while the latest instalment Bahnsen Knights is a gumshoe thriller that plays off the Satanic Panic of the 1970s. The studio’s specific brand of nostalgia makes me yearn for an ephemeral time, place, or feeling rather than a specific game or gaming era, and that’s what makes Pixel Pulps stand out amid the current indie horror boom.

We are Legion

And what a boom it is, indie or otherwise. Despite drawing most of its inspiration from horror fiction rather than video games, the LCB duo understands how and why horror works in games as developers, novelists, and as fans of such an active genre themselves. Knowing this allows LCB to hone in on the Pixel Pulps’ unique selling point as predominantly literary game experiences.

“Remakes are more about business than creation,” LCB says. “Nowadays it is difficult to launch a new game, and in the remake there is a shortcut, a way to stand on the shoulders of a giant so that the public can see you and choose you. In our case the strategy is different. We create all new IPs, under the Pixel Pulps umbrella, and our goal is to become the Pulps of interactive fiction.” Having launched three games in a year and a half, and with two unannounced titles on the way (including an 80s slasher-tinged entry), LCB says the grind is all part of the process. “By publishing so much we believe, perhaps innocently, that we increase our chances of raising our voice above the general noise, like someone who buys dozens of lottery tickets to try to beat the big numbers of statistics.”

“Horror is the alchemist’s secret, if you will.”

LCB Game Studio

Steam is teeming with horror games of all shapes, sizes, and permutations as we dig deeper into 2024, and LCB agrees that this resurgence isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. A thriving scene means plenty of competition, though, and that battle rides on a lot more than nostalgia plays and genre-specific kitsch alone.

“Horror in video games can be a trap,” says LCB, “A genre in which it is easier than others to dump design elements such as tank control systems, camera systems, reductionist explanations of a character’s motivation translated into a pathfinding algorithm, gimmicky level design, and more.” The studio hazards a guess that the supposed ease of making a horror game is both a blessing and a curse, drawing more developers to the genre thanks to “a whole system of consumption and feedback between streamers and the genre” already being in place. This feedback loop is part of how indie horror has carved out such a vibrant space for communities and creators in the first place, after all, but LCB doesn’t want to rest on those laurels.

“While this [system] has a huge value for the industry, [horror] can also be a place to experiment more, to create deeper, more memorable stories,” says LCB on horror’s ongoing evolution and the studio’s part in it. “That’s what we want from horror in video games: we want more original IPs, even more stories that do not let us sleep, either by fear, or by not being able to stop experiencing them.”

Check out the best horror demos of Steam Next Fest, from survival horror to tech noir terrors.

[ad_2]

Source link